We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies.

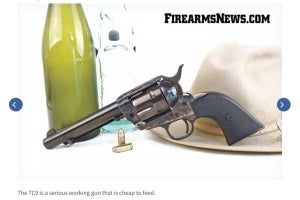

The Taylor’s & Company 1875 Outlaw 9mm Revolver

Article Posted On RevolverGuy.Com By Steven Tracy

https://revolverguy.com/the-taylors-company-1875-outlaw-9mm-revolver/#more-13040

I was enamored with the Taylor’s & Company 1875 Outlaw single action revolver from the moment I first handled it. I can’t remember the last time I was captivated so quickly. The deep blue finish on the all steel handgun was strikingly handsome in the light as I removed it from its box. The polished finish was dark, but not black like many of today’s modern guns. Instead, it had that old world appearance that matched its 1875 style.

I first learned about the Remington 1875 single action revolver through my dad’s extensive library of firearms books and gun magazines. Original Remington revolvers have never been common and I don’t recall having seen a real one in person. I couldn’t help but wonder how the grip would feel compared to a Colt 1873 or a Ruger Blackhawk. The 1875’s grip looked to have a little more room between the rear of the trigger guard and where the underside of the steel grip frame curved downward. Or maybe it was just an optical illusion caused by the way the grip frame extended more rearward compared to a Colt’s. The wood grips truncated further back and gave the 1875 a unique appearance.

I’d never held one…but that was going to change.

TAYLOR’S AND THE METRIC SYSTEM

Mike reviewed the Taylor’s & Company 1873 TC9 a short time ago and we talked about its attributes together. Shooting 9mm cartridges in a single action hits all the green buttons on my console. 115-grain 9mm factory practice rounds are the least expensive centerfire cartridges available at retail or mail order prices. Shooting the 9mm equals more rounds downrange per dollar spent. The 9mm’s recoil is relatively mild and a heavy, steel framed single action style revolver tames it easily.

Because of the single action revolver’s design, loading and unloading the chambers with 9mm ammo is just as straightforward as any other cartridge that such guns have historically been chambered for (such as .45, .44-40, etc). Ruger has offered their Blackhawk single action chambered in .357 Magnum that comes with an extra 9mm cylinder for several years and they’re all kinds of inexpensive fun to shoot. Friends who own them told me they enjoy shooting the 9mm more than the .357/.38 cylinder.

The conversations Mike and I had resulted in me ordering a 5 1/2-inch version of Taylor’s new 1875 Outlaw with hopes that it would fit in some of my similar-sized holsters made for Colts and Rugers. Taylor’s also offers a Taylor’s-Tuned 7 1/2-inch model, but I only have one holster for the longer barrel length and I much prefer the handier shorter barrel. For now however, an even shorter barrel (around 4 3/4-inch like a Colt or 4 5/8-inch like a Ruger) is not available in the 1875.

The (usually) semi-automatic 9mm Parabellum cartridge is likely the most used center fire cartridge in the world. Shooting it in a handgun design dating back to the 1870s is a grand idea.

FIT AND FINISH

This 1875 replica is manufactured in Italy by Uberti and imported by Taylor’s & Company to their own specifications. Uberti has been making replica revolvers since 1959 and quality has been consistently upgraded over the years. I owned a Cimarron (another importer) 1873 .45 Colt I bought around 1990 that was made by Uberti. The action was rough and fit and finish was riddled with imperfections. I purchased a Cimarron 1872 Open Top .44 Special in 2012 and it was much improved. The factory action needed some work, but the gun’s appearance was impressive. My expectations ran high for this new Taylor’s 1875.

I’ve read reviews of current production lever action and bolt action rifles where the wood to metal fit was described as very good. I’ve seen the guns myself and I’ve run my finger over the line where the wood meets up with the metal and I just about tore a fingernail off because of the huge gap or gargantuan height difference between the two. I wondered, “Has the reviewer ever seen and handled an original Winchester or Remington or Marlin from the 1800s?” Because back then the artisans working at the factories carefully hand fitted the stocks to the guns and the transition was smooth and imperceptible between wood and steel. There were no discernible bumps or ridges on those antique firearms.

The walnut used on the Italian made Ubertis has always impressed me with its richness and color. The stocks on this 1875 are handsome and complement the blue finish. They are hand fitted like they were 150 years ago. The wood meets seamlessly with the front and back of the trigger guard and at the bottom of the grip frame. The sides of the grip frame are comfortable in your hand because they are hand fitted so perfectly. The polished oil finish on the grips looks rich and lustrous. Instead of being dull or satin, its shine matches the polished steel. All of the revolver’s edges are sharp where they should be and rounded with their edges broken where they needed to be.

SMOOTH ACTION AND LIGHT TRIGGER

On their website, Taylor’s lists several of their firearms as “Taylor Tuned” (including this particular 1875 9mm). The suggested retail price of a Taylor Tuned gun is around $150 more than the same gun without the tag. It further states that some standard guns in stock can have this service added. It includes a hand polished action and custom springs installed by a Taylor’s gunsmith.

My 1875 was Taylor Tuned and the result is impressive and well worth the fee. You would be hard pressed to find a quality gunsmith to perform this service for this price. I opened the loading gate and drew the hammer back two audible clicks to place it on half cock. I inspected each of the six cylinder chambers to make sure the revolver was unloaded. Then I closed the loading gate and drew the hammer back two more clicks until it was fully cocked. This is the proper procedure for any single action revolver. The hammer should never be lowered from the half cock position, but rather fully cocked before releasing the hammer (with your thumb easing the hammer down) by pulling the trigger.

I stared carefully through the gap between the frame and the cylinder from its right side. I observed the bolt immediately disappear into the bottom of the frame when the hammer was first cocked. Then, as the cylinder rotated while the hammer continued to be drawn back, the bolt stayed tucked away from contacting the cylinder until the very last moment when the hammer was all the way back. Only then did the bolt raise back up into the cylinder stop notch. The timing on this 1875’s action was perfect. Even after extensive firing, the cylinder was not scored with a “turn line” because the bolt only settled into the notches where it was supposed to.

Cocking the hammer was lighter on this 1875 than most factory single actions from any manufacturer I can think of. Strong springs are necessary to ignite primers, but some revolvers have factory hammers with very strong main springs that make the guns difficult to cock easily. This 1875’s color case hardened hammer, with crisscrossed cut checkering where your thumb makes contact, was easy to thumb back. The hammer’s checkering is not deep (like they were 150 years ago) but it works and provides a texture that prevents slippage.

The hammer has a firing pin retained in its face. It is not a one-piece hammer/firing pin, but rather a separate firing pin that is secured in the face of the hammer. Since there is no transfer bar, this 1875 must be carried with only five rounds loaded in its cylinder and with its hammer resting on an empty chamber. Do not be mislead by the safety device on the inside face of the hammer that can be seen when cocked. It is there to allow importation to the US by passing a drop test. The mechanism is not a transfer bar. It is there for one time use to prevent the gun from going off if in case the hammer is struck with a loaded round under its nose.

The trigger on this 1875 is wider than the thin width of the Colt 1873’s. The Colt trigger has always felt too narrow when the tip of my index finger presses it. This 1875 feels just fine and it works even better! While dry firing with the revolver unloaded, I was impressed with how light it felt. A Lyman digital trigger pull gauge confirmed that the trigger breaks at a mere 2.5 pounds. That’s just perfect! It’s light enough not to disturb the sight picture when shooting, while the hammer’s fall is strong enough to ignite even the hardest of primers.

LOADING AND UNLOADING

The proper and easy way to load your five shots in the 1875’s cylinder is to insert a round into the first chamber, rotate the cylinder to skip the second chamber, then load the next four, then cock the hammer all the way before pulling the trigger and easing the hammer back down on the empty chamber (watching carefully to make sure it was done right).

Despite this particular gun’s 9mm chambering, it loads and unloads like every other similarly styled single action. When dropping a cartridge into the cylinder chamber through the open loading gate, the case mouth catches on a lip inside the chamber. This prevents the round from falling out the front of the cylinder and keeps it right where it is supposed to be. There is no rim on the 9mm like there is on a revolver cartridge, but the system works perfectly.

Ejection of spent cases is accomplished by pushing the ejector rod mounted under and to the right of the barrel. The crescent shaped ejector rod head is mounted far forward, closer to the muzzle than a Colt’s. Underneath the barrel is a steel web that harkens back to the Remington 1858’s loading lever. This 1875 retains that cap and ball revolver’s pivoting lever look, likely to differentiate it from the Colt 1873 back when both were still new. This revolver’s under web is just for show, but it does help a bit in guiding the gun back during re-holstering.

I removed the two piece walnut stocks to reveal the leaf style main spring inside the grip frame. The grips slip carefully under the front top area of the grip frame, utilizing a sort of dovetail for a tight fit.

SIGHTS AND SHOOTING

The sights are fixed, as is typical of revolvers originally designed 150 years ago. The front blade narrows slightly towards its top, but is easy to align within the rear frame’s notch, which is squared off. This system has worked well since its inception, despite the much larger target style sights of today.

The trick with fixed sights can be when they don’t shoot to point of aim. The only way to properly regulate the front sight on a revolver of this type is to twist the barrel in the frame with a device to turn the front sight left or right. Most shooters learn if their gun hits left or right and then employ the “Kentucky windage” technique of holding a bit left or right in order to hit in the middle. Front sights were made tall back in the day so that they could be filed down to get them to hit center at certain desired distances. Some shooters have attempted to bend their front sights left or right and that has often resulted in a front sight that fell off eventually. They’re really hard to hit with when that happens.

I was well aware of the pitfalls of fixed sight, cowboy style revolvers, so I was more than pleased when this 1875’s hits proved to be dead on, needing no adjustment or utilization of Kentucky windage. My smile couldn’t have been bigger after I fired my first shots off a rest at a paper bullseye target.

Because I would primarily be shooting this single action for fun, I had the three most common 9mm full bullet weights on hand (as offered as factory loadings). 115-, 124-, and 147- grain full metal jacket bullets are also usually the least expensive to purchase, while the 115-grain rounds provide the least felt recoil.

CCI/Speer’s Blazer Brass 115-grain full metal jacket was the first ammo I fired. I set my bullseye targets at 15 yards (45 feet) and aimed using a 6 0’clock hold as best as my aging eyes could align the sights. Aiming at the bottom (6 o’clock) of the black bullseye circle allows the dark sights to contrast with the white paper much better than trying to see them on the black bullseye.

I lined the sights up while using a Hy-Score handgun rest and cocked the hammer. I was happy with the Taylor’s 1875’s action and trigger, but I was ecstatic when I started to shoot and couldn’t see any hits appearing on the white portion of the paper target. Why was I happy to not be able to see my shots? Because all five shots hit their mark in the black of the bullseye where they were difficult to see 15 yards away.

As I continued to shoot various 9mm bullet weights and styles from several different makers, it became apparent that this single action liked lighter and faster bullets. They were consistently packed into tighter groups. The 124- and 147 grain 9mm cartridges still grouped well, but the 115-grain rounds were tighter and the non-lead, 50-grain Liberty Civil Defense ammunition fired the best group of five rounds.

When Mike shot his Taylor’s 1873 9mm, it shot low because the front sight was tall. Apparently the front sight height on this Remington replica is just right for using a 6 o’clock hold at 15 yards with the right bullet/load.

I even fired a blue CCI 9mm shotshell on target at two yards away, known as the “venomous snake” dispatching distance. The shot pattern was impressive and would be even more impressive to a dangerous snake.

Each cylinder chamber of the 9mm 1875 has a ridge machined inside that catches the mouth of the cartridge’s case. This prevents the rimless ammunition from falling out the front of the cylinder. It headspaces each round properly for its primer to be struck by the firing pin. No remaining bullets were pulled from their cases under recoil as the gun was fired and shooting it was no different than firing any other regular rimmed revolver round.

HANDLING AND CARRY

The original Remington 1875 competed with the Colt 1873 (Single Action Army Model P) when it first came out. It carried over the looks of the well regarded Remington 1858 black powder cap and ball revolver by retaining the steel web underneath the barrel that mimicked the 1858’s loading lever. This Taylor’s 1875 weights 2.5 pounds with its 5 1/2-inch barrel and 9mm cylinder chambers and bore. The original guns were chambered in .44 Remington, .44-40, and .45 Colt, so modern day versions in .45 weigh less than .357 or 9mm models with more steel due to their smaller diameter bores.

The web under the barrel also adds weight and all of that heft make the 9mm round feel docile when fired. Even the hottest loads were easy to handle. While some velocity is lost when the bullet jumps the gap from the cylinder into the barrel (compared to a semi-automatic pistol), the 5.5-inch barrel length likely helps maintain the 9mm round’s performance. That translates to the 1875 being up for serious self defense against man or beast. If the 9mm is your choice of defensive caliber, then this 1875 from Taylor’s can certainly get the job done as well as any semi-automatic pistol.

The grip is slightly different than other single action revolvers. It’s just a bit longer behind the trigger guard than a Colt 1873’s. My big hand fits a little too tight in a Colt’s or Ruger’s standard grip, but it felt great in the 1875 Outlaw’s. I’ve owned and shot pretty much every common single action grip style there is. The Colt Bisley raps my knuckles something fierce and even the Ruger Bisley grip will smack my middle finger knuckle painfully when firing the hotter cartridges. I’ve never shot a Merwin and Hulbert, but it’s grip looks awfully small. The Colt 1860 Army grip (like the one on Mike’s Taylor’s 1873 that he reviewed) is plenty big and works great for me. I like this 1875’s grip just fine.

The Outlaw fit in all of the leather holsters I had that were made to fit my 5 1/2-inch Colts or Rugers, despite the web under the 1875’s barrel. So if you already have a holster for a Colt or Ruger, you’re good to go if you get yourself an 1875. If you want to order a holster from a maker and they don’t list the Remington 1875, I’m just letting you know that a Colt or Ruger holster will work just fine.

When I drive around the fields and woods in my Polaris side by side, I prefer a cross draw holster when seated. It’s easy to draw from and the muzzle doesn’t poke down into the seat like a strong side holster can. Even when just walking out on our property, a cross draw carries well for me. The 1875’s weight was distributed well in either a cross draw or a strong side holster. I utilized the Threepersons style of both types, along with various other western style holsters on my dominant right side hip.

Loaded with four Civil Defense 9mm cartridges from Liberty and a CCI shotshell (the snake load being first up when cocking the hammer), I was armed for venomous snakes or almost anything else my area of West Tennessee might present to me. We did see a mountain lion this last September while driving about a half hour away. The 9mm might be a bit light for a cougar, but the saying about mountain lions is that it doesn’t matter what caliber you carry, because if one attacks, it’ll be too late…you’ll have never known it was there anyway.

THE HISTORY

The Remington 1875 went by many names, including the 1874 as it was first referred to by Remington in their catalog that came out in 1875. The next year it was called the Remington No. 3 Revolver, Model 1875. Remington Improved Army and Frontier Army were also used during the gun’s production years. Advertising was important back in the 1800s and titles, names, and claims were carefully planned when describing products. The revolver was first chambered in .44 Remington and then .44-40 and finally the .45 Colt cartridge, but the last one was only referred to as the .45 Government in Remington advertising. The Remington New Model Army Revolver became the referenced name another year or two later in factory brochures.

Model 1888 and 1890 versions were produced by the new owners of Remington in those years. The mechanics of the gun remained the same, but the distinctive web under the barrel was eliminated.

Frank James, member of the James-Younger gang, is historically known to have carried a .45 caliber Remington 1875, which he turned over to the Governor of Missouri when he surrendered. His older brother Jesse James and Buffalo Bill Cody owned 1875s, but were not known to make general use of the revolver.

Original 1875s had a lanyard ring attached to the bottom of the grip frame on early guns (which also used a post front sight) and as an option as time went by, but the Taylor’s does not include this feature. I would most likely never use it anyway so it matters little to me that it is missing.

Remington sold 650 1875s to the US government for use by the Indian police and another 1000 to the Mexican government. An order of 40,000 to Egypt never came to fruition.

PARTING SHOTS

I used to participate in Cowboy Action Shooting through a local Single Action Shooting Society (SASS) club and I enjoyed every second of it. I’m lucky to now have my own steel target range here in Tennessee and I enjoyed putting this new Taylor’s 1875 to the test. Keep in mind that a fixed sight, single action revolver was never meant to be a game getter at 50 yards. It wasn’t designed as a hunting revolver. It was meant to be a defensive firearm, handy at your side in a holster. It was also meant to be used at distances most likely taking place during a gunfight.

I stood facing my orange spray painted steel targets. I have 2×4 spikes driven into the ground at 21 feet and also spray painted orange so I know the distance to the steel. The 1875 was on my side in a Threepersons holster by El Paso Saddlery. The leather was floral carved. I drew and fired five rounds, the 9mm revolver barely recoiling in my hand. Thumb cocking each shot was smooth and easy due to the Taylor Tuned action and the trigger pull never disturbed the sights.

Each shot rang the steel plates in the bright sun and it really seemed I could not miss. I opened the loading gate, pulled the hammer back two clicks, twisted the blued steel revolver in my hand so I could rotate the cylinder with my fingers, and used my right hand to press the long ejector rod to knock the spent 9mm casings out onto the grass. I dropped five fresh cartridges into the cylinder (load one, skip one, load four) and went to work again.

The fresh orange paint gave way to the gray steel underneath, but the blotch had no stray, single impacts. The grouping was superb. I gave all the credit to the gun and not to myself.

The grip is so similar to that of the Colt SAA that I didn’t notice any big difference. That little bit of extra room behind the trigger guard gave my big knuckles some room to move when needed. The plow handle tipped back in my palm under the 9mm’s slight recoil and the smooth walnut stocks let the gun slip without sandpapering my skin. The hammer was positioned for thumb cocking and the muzzle came back on target for successive shots intuitively.

There is just something special to us RevolverGuys about firing a single action revolver. It’s got a lot to do with western television shows and movies and the good guy heroes portrayed in white cowboy hats. There is an interaction between man and tool that all revolvers have that semi-automatic pistols do not. The manual cocking of the hammer makes the single action all the more inspiring to the gun owner’s soul. There is also something about harkening back to a different time and lifestyle 150 years ago. At least for me there sure is.

Shooting this Taylor’s & Company 1875 is made even more enjoyable because I can afford the ammo to shoot it more regularly. I think it will be a fun gun for friends and family to shoot when they visit and I take them out to my range. Everyone likes to shoot single actions!